Weighing The Balances – Pros And Cons Of BRICS And Western Engagement

Introduction

Building upon the regional analyses in Article 7—where bodies such as the African Union (AU), Southern African Development Community (SADC), Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), and Alliance of Sahel States (AES) demonstrated collective strategies for navigating BRICS and Western influences—this eighth instalment evaluates the advantages and disadvantages of engaging with these global blocs from an African perspective. As BRICS, now with 11 full members including three African nations (South Africa, Egypt, and Ethiopia), advances its agenda post the 2025 Rio Summit, and Western institutions like the European Union (EU) and United States (US) respond with initiatives amid escalating tariffs under the second Trump administration, African states must assess these engagements critically. This evaluation reveals opportunities for economic diversification and technological advancement alongside risks of dependency and geopolitical entanglement.

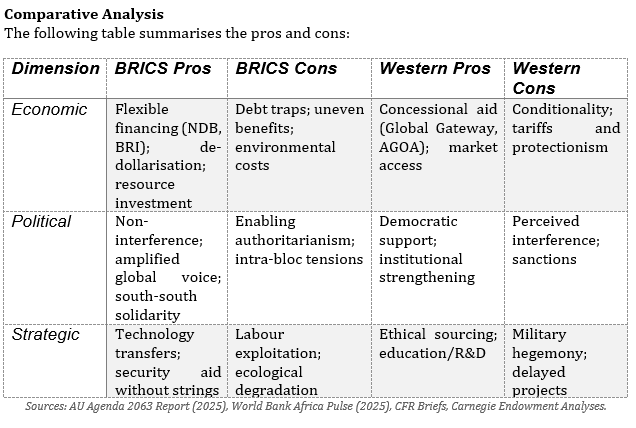

Drawing on reports from the AU, World Bank, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Council on Foreign Relations (CFR), and the 2025 Africa Integration Report, this article dissects the pros and cons of BRICS and Western engagements across economic, political, and strategic dimensions. It emphasises African agency in leveraging these dynamics to support frameworks like the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) and Agenda 2063, while avoiding binary framings. This balanced assessment prepares the ground for Article 9’s focus on pathways to self-reliance.

Pros of Engagement with BRICS

BRICS offers African nations alternative pathways for development, characterised by non-interference, flexible financing, and south-south cooperation, which align with continental priorities for sovereignty and equity.

Economically, BRICS provides access to substantial investments without stringent conditionalities. The New Development Bank (NDB), established in 2015, has disbursed over USD 35 billion globally by 2025, with Africa receiving approximately 20% for infrastructure projects. For instance, Ethiopia’s Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) has benefited from NDB funding, enhancing energy security and supporting industrialisation under Agenda 2063. China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), integral to BRICS, has invested USD 250 billion in African infrastructure since 2013, including railways in Kenya and ports in Djibouti, boosting intra-African trade projected to reach 35% by 2025 via AfCFTA integration. De-dollarisation efforts, accelerated at the 2025 Rio Summit, enable local currency trade, shielding African economies from US tariff hikes—averaging 27% by April 2025—and reducing vulnerability to Western sanctions.

Politically, BRICS amplifies African voices in global governance. With South Africa hosting the G20 in 2025 and advocating UN Security Council reforms, the bloc supports Africa’s push for two permanent seats, fostering multipolarity. Russia’s engagements in the Sahel, through the Africa Corps, provide security assistance without governance demands, aiding AES countries in combating jihadism. This contrasts with Western approaches, allowing African states to maintain non-aligned stances, as seen in Nigeria’s BRICS partnership facilitating debt restructuring.

Strategically, BRICS promotes technology transfers and resource sovereignty. India’s pharmaceutical collaborations have supplied affordable generics to over 60% of African markets by 2025, addressing health challenges amid climate-induced diseases. Brazil’s agricultural expertise supports food security initiatives, while the bloc’s focus on critical minerals—Africa holds 30% of global reserves—enables value-added processing, reducing raw export dependencies.

Cons of Engagement with BRICS

Despite these benefits, BRICS engagements pose challenges, including debt accumulation, environmental concerns, and intra-bloc rivalries that may spill over to Africa.

Economically, high-interest loans from BRICS institutions, particularly China, have led to debt distress in some nations. By 2025, African debt to China stands at USD 150 billion, with Zambia’s 2023 restructuring highlighting repayment burdens exacerbated by commodity price fluctuations. The 2025 US tariffs have indirectly strained BRICS-Africa trade, as retaliatory measures increase costs for African exporters reliant on Chinese markets. Moreover, uneven benefits—concentrated in resource-rich countries like South Africa and Nigeria—widen intra-African inequalities, hindering AfCFTA’s equitable implementation.

Politically, BRICS’ non-interference can enable authoritarian tendencies. Russian support for Sahel juntas, while providing security, has been criticised for overlooking human rights, potentially destabilising regions as seen in AES-ECOWAS rifts. Intra-BRICS tensions, such as China-India border disputes noted in Article 2, could fragment the bloc’s cohesion, reducing its reliability for African advocacy in forums like the WTO.

Strategically, environmental and social impacts are notable. BRI projects have faced scrutiny for ecological degradation, with deforestation in Congo Basin mining areas linked to Chinese investments. Labour issues, including exploitation in construction, undermine local empowerment, contrasting with Agenda 2063’s sustainability goals.

Pros of Engagement with the West

Western engagements, through institutions like the EU, US, and World Bank, offer structured support emphasising governance, sustainability, and market access, complementing African development agendas.

Economically, Western initiatives provide concessional financing and trade preferences. The EU’s Global Gateway has mobilised EUR 150 billion for Africa by 2025, funding green infrastructure like solar farms in Morocco, aligning with climate resilience under Agenda 2063. The US African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), extended to 2030 amid tariff escalations, grants duty-free access for exports from 35 African countries, generating USD 10 billion in trade annually. World Bank loans, totalling USD 50 billion in 2025, support macroeconomic reforms in nations like Kenya, fostering private sector growth and digital economies.

Politically, Western partnerships promote democratic norms and institutional strengthening. EU-AU dialogues have advanced peacekeeping, with EUR 5 billion allocated to AU missions in Somalia by 2025. US engagements via AFRICOM enhance counterterrorism capacities, as in Nigeria’s operations against Boko Haram, while supporting electoral processes to bolster stability.

Strategically, technology and education transfers are key strengths. Western scholarships and R&D collaborations, such as US-funded STEM programmes, have trained over 100,000 African professionals by 2025, aiding innovation. Investments in critical minerals emphasise ethical sourcing, with EU standards reducing conflict risks in the DRC.

Cons of Engagement with the West

Western engagements, however, carry legacies of conditionality and perceived neo-colonialism, potentially undermining African sovereignty.

Economically, aid is often tied to reforms that prioritise Western interests. IMF structural adjustments have led to austerity measures, exacerbating inequalities in countries like Ghana, where 2025 debt negotiations imposed fiscal cuts amid US tariff pressures. The second Trump administration’s tariffs—30% on South African goods—have disrupted supply chains, costing Africa USD 20 billion in exports by October 2025, highlighting protectionism.

Politically, interventions can foster dependency and interference. US sanctions on Russian-African ties have strained neutral stances, while EU migration deals, like those with Morocco, prioritise European security over African mobility rights. Historical contexts from Article 3 underscore perceptions of paternalism, eroding trust.

Strategically, military footprints raise concerns. AFRICOM’s presence, relocated from Niger in 2025, is viewed as hegemonic, potentially escalating conflicts as in Sudan. Environmental conditionalities, while beneficial, can delay projects, hindering urgent development needs.

Implications for African Self-Reliance

Weighing these balances, African engagements with BRICS and the West can advance self-reliance if approached pragmatically. Diversification—leveraging BRICS for infrastructure and the West for governance—mitigates risks, as exemplified by South Africa’s G20 hosting. However, fragmentations from tariffs and bloc rivalries, echoing Article 5’s geopolitical contest, necessitate stronger Pan-African mechanisms. By prioritising AfCFTA, Africa can transform external dependencies into internal strengths, fostering equitable growth.

Conclusion

The pros and cons of BRICS and Western engagements underscore Africa’s strategic position in multipolarity. BRICS offers autonomy and rapid development, tempered by debt and environmental risks, while the West provides structured support amid conditionalities and tariffs. This mosaic, informed by country and regional alignments in Articles 6 and 7, highlights the need for balanced strategies. As the continent navigates these dynamics, the focus shifts to self-reliance pathways in Article 9, emphasising AfCFTA and Agenda 2063 to secure sovereignty and prosperity.